Studieren in Aarhus und Weimar

Transparency and Flexibility

Iaroslava Komissarova studies architecture at the Aarhus School of Architecture. She is in the second year of her master degree. The bachelor‘s degree she completed at MARCH school in Moscow.

Foto: Iaroslava Komissarova

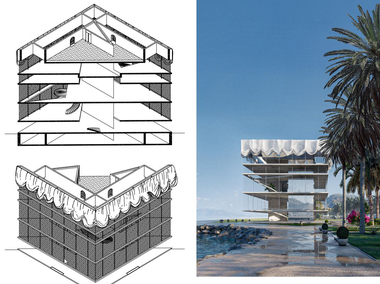

Located at a former rail yard, the new building of the Aarhus School of Architecture has formed a point of attraction for the entire city. It rejects the form-function-opposition and turns out to be a product of careful observation of architects „in their natural habitat“. It may be what the philosopher Immanuel Kant called a „Ding an sich“(“thing-in-itself”). Study, transformation, experimentation, transfer — each of these terms refers to the inner composition of the new school. The design of the environment is in itself a generator of new architectural meanings.

The simplicity of the external composition is absolutely leveled by the complexity of the internal organization. Every space of the school is a „tabula rasa“ for our experiments. Six concrete cores give rise to a forced movement between the main locations — a kind of embodiment of interaction between participants in the educational process. This seems to be familiar to everyone who has moved around the school. You often catch yourself thinking that you have got into a new space, not understanding how it has happened.

The dynamism of the school also applies to individual student projects. We have ten different fabrication labs at our disposal. Thus we have the possibility for example to assemble a wooden model on a scale of 1:1, to cut out different prototypes on a Zund Laser Cutter Machine or to use the Robot Lab. Being part of the process of various experimental areas and workshops gives us the freedom to implement completely different ideas.

The raw architecture, referring to the typology of an industrial building, is delicately softened in wooden details, bringing empty space to the fore. The pandemic has highlighted the need for distance. However, with the easing of covid restrictions, the apparent need for the physical co-presence of others has increased. The new building of the Aarhus School of Architecture is a showcase for an institution where many spontaneous encounters once again become possible, where people study, work and crowd together. It is made by architects for the needs of architecture students, and its apparent simplicity and openness is the answer to the demand for flexibility today.

Foto: Iaroslava Komissarova

Transparency outside and inside

The new school offers different platforms for research, but it also acts as an experiment itself. Functional zoning is thought out in such a way that the activities inside become visible to the public. The workshops located on the ground floor do not seem isolated. Thanks to the literal transparency they are part of both the school process and the city event. The remaining sites are also functionally flexible — the dining area is marked only with wooden tables, and the two main lecture halls become such only when plastic chairs are placed. The difficulty in defining boundaries is the most intriguing part of the mixed-use building. Each time questioning the rules of space use, the new building encourages synergy and openness to inventing your own boundaries of use. Observation becomes another tool for using space, showing how the gears of the workflow are spinning. What is common and what is private? Does my private space end with the perimeter of my desktop, or can privacy extend to the entire architecture studio of a particular course.

Despite the similarity to a manufactory, it is first and foremost a school, ready not only to offer spaces for learning, but also to carry educational initiatives. By exposing the principles of tectonics, engineering and materials science, the building becomes the material alphabet of a novice architect. For those who are especially attentive, miniature drawings of various structural details are prepared on each door.

Despite the inherent flexibility, there is still one space with a single function — the library — the heart of any educational institution. The AAA in partnership with Praksis Arkitekter built a huge wooden structure called Mediatek based on the principles of sustainable design. It reinvents the grid, building a communication system completely different from other spaces in the school. Partially formed by the shelving carefully selected from a nearby historic building, the library is part of an environmental initiative for reusing material.

The Aarhus School of Architecture brings isolated and insular school institutions together that had existed for more than 50 years. But it also allowed itself to go further by turning the learning process inside out. Offering transparency and encouraging the formation of communities, it has become a kind of manifesto for a new architectural education in Denmark.

Werkstatt und Weltkulturerbe

Antonia Stuhm hat im Sommer 2022 den Bachelor in Architektur an der Bauhaus-Universität in Weimar absolviert. Mona Thoma studieren Architektur im 5. Master-Semester an der Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. Sie hat den Bachelor an der TU Berlin abgeschlossen.

Foto: Antonia Stuhm, Mona Thoma

Das Hauptgebäude der Bauhaus-Universität Weimar wurde Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts von Henry van de Velde als Ateliergebäude für die Großherzoglich Sächsische Hochschule für bildende Kunst in Weimar erbaut. Somit ist es ursprünglich als Kunst- und Bildhauerschule geplant worden. Heute befindet sich hier der Sitz der Fakultät Architektur und Urbanistik. Es ist eines von vielen Gebäuden der heutigen Universität. Seit seiner Entstehung während des Kaiserreichs ist es immer ein Ort des Lehrens und Lernens geblieben, der Kreativität und des Schaffens. Als erstes Hochschulgebäude des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar ist es zudem ein vielfach besichtigtes Bauwerk von Kunst- und Architekturinteressierten. Das Hauptgebäude mit seinem dem 20. Jahrhundert entsprechenden repräsentativen Charakter zeigt die Anforderungen an ein Hochschulgebäue der damaligen Zeit. Das Aufeinandertreffen von Lehre und Historie, von Werkstatt und Weltkulturerbe schafft ein Spannungsfeld, in dem wir uns täglich bewegen.

Der gelbe Putz

Entgegen der Vorstellungen vieler Besucher:innen, die sich durch die Assoziation mit dem Bauhaus einen aus Glas, Stahl und Beton minimalistisch gestalteten Kubus vorstellen, zeichnet sich das Gebäude von außen betrachtet durch die großen Atelierfenster, das rote Mansardendach und seinen gelben Putz aus. Damit reiht es sich in den Farbkanon der pastellfarbenen Stadtfassaden ein.

Das Foyer

Über ein paar Stufen erreicht man den Haupteingang und betritt durch den orangefarbenen Windfang das Foyer. Die Infotheke mit bunten Flyern und Plakaten erinnert an den Eingang eines Museums. Der hohe Raum beherbergt die „Eva“, eine von Auguste Rodin angefertigte Bronzeskulptur. Die kleine Ausstellung wird fortgeführt: zwei Wandreliefe und die beiden Büsten von Gropius und Van de Velde befinden sich in Wandnischen. Die ikonische, elliptisch geformte Freitreppe lädt ins Gebäude ein.

Das Atelier

Großformatige Atelierfenster, beeindruckende Raumhöhen, ein Keramikwaschbecken in der Ecke – Elemente, die unsere Ateliers prägen. Die doppelflügeligen Türen knarzen, wenn man sie zu langsam öffnet. Nach wie vor sind die Arbeitsplätze in den Ateliers sehr beliebt. 2019, das 100-jährige Bauhaus-Jubiläum. Nicht selten wird die Tür zum Atelier aufgerissen, eine Gruppe Touristen möchte sich die Räumlichkeiten anschauen, sie fotografieren. Es wird ein leeres Marmeladenglas aufgestellt, „Trinkgeld“, darunter auf Englisch „Tips“. Am Ende kam genug Geld zusammen für einen Kasten Bier. 2020, ein abrupter Bruch. Durch die Schließung der Universität sehen viele Student:innen die Arbeitsräume erst zwölf Monate nach Studienbeginn zum ersten Mal. Die eigene Küche wird in den Wintermonaten zum Atelier auf Zeit.

Foto: Antonia Stuhm, Mona Thoma

Das braune Linoleum

Der Boden aus braunem Linoleum zieht sich durch das ganze Gebäude. Er ist schon etwas zerkratzt. Nach dem Wintersemester werden die Kratzer weiß hervorgehoben. Die Gipsmodelle haben sich in den Ritzen verewigt. Diese kleinen Gipskratzer werden zu einer der wenigen Spuren, die man als Student:innen in dem Denkmal zurücklassen wird.

Die winzige Toilette

Die Suche nach der Frauentoilette im 2. OG endet in einer Kammer am Ende des Flurs. Es scheint fast so, als sei kein anderer Platz für sie gefunden worden. Wie eine kleine Kiste sitzt sie im Gang. Kompakt, ungewohnt niedrig, mit einem Waschbecken und einer einzigen Kabine ausgestattet. Lediglich der Türgriff aus Messing und der Boden aus Terrazzo schmücken den Raum.

Das Mobiliar

Die zum Anfang des Semesters hoch aufgestapelten schwarzen Egon-Eiermann-Gestelle ergeben das Bild einer Kunstinstallation. Eine intensive Suche nach der perfekten Kombination aus Gestell und Tischplatte beginnt. Blaue Flecken auf den Schienbeinen zeugen vom Zusammenstoß mit dem Kreuzgestell. Kaum eine Platte ist dem Cuttermesser einer ungeduldigen Student:in entkommen – es muss „nur schnell“ etwas zurechtgeschnitten werden.

Ecken und Nischen

Pro Etage ein langer Flur mit Räumen, die sich aneinanderreihen. Das Verständnis von Lehre hat sich verändert – gemeinschaftliche Zonen und Bereiche zur Aneignung gibt es kaum. Doch hier und da bildet die Fassade Fensternischen aus, uneinsehbare Ecken wurden über die Zeit zu kleinen Orten des persönlichen Rückzugs. Hier spricht man sich gut zu, tauscht sich aus. Hier kann man ungestört telefonieren. „Vielleicht wird es heute etwas länger.“

Foto: Antonia Stuhm, Mona Thoma