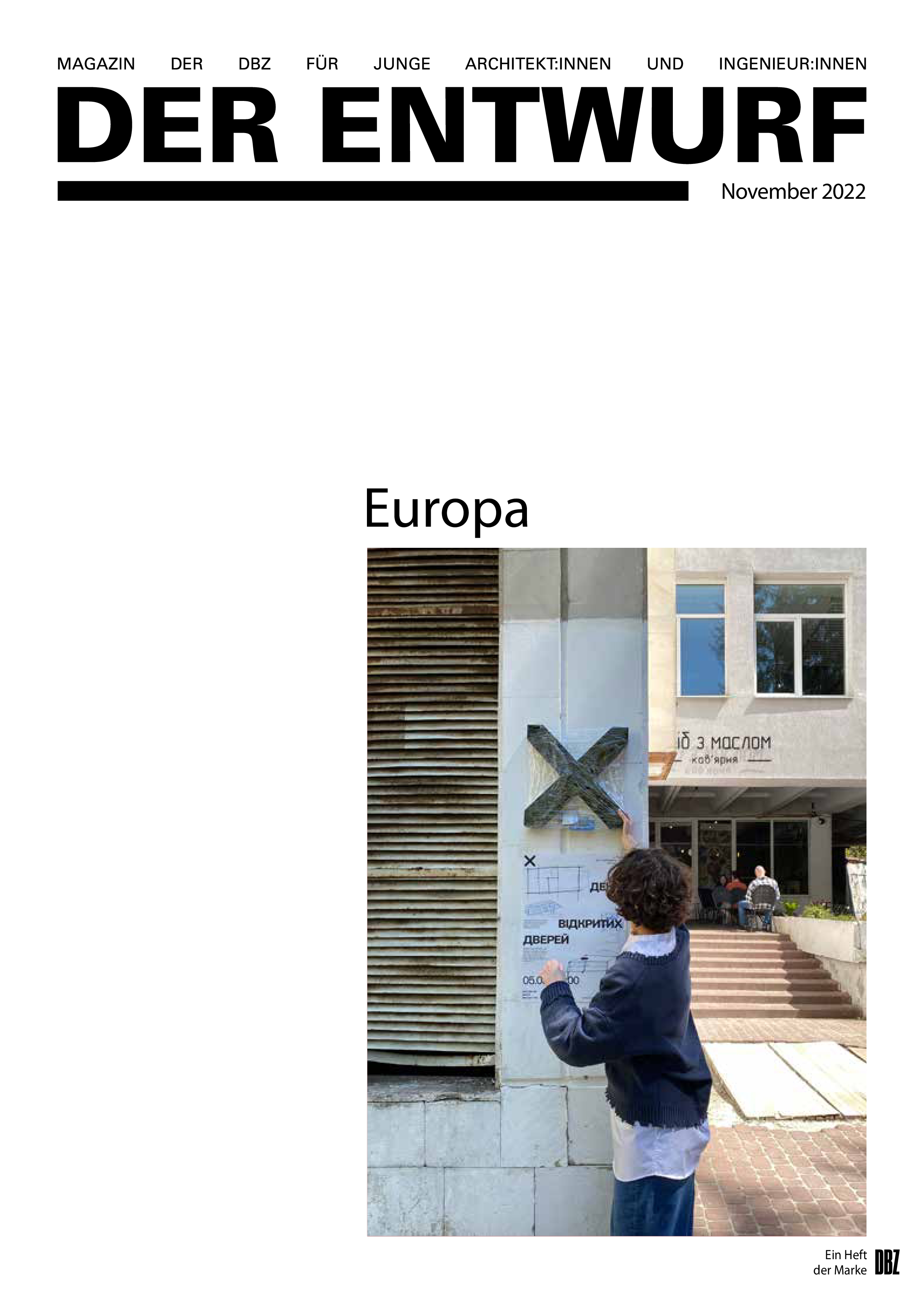

Placement of the logo of KhSA on the building of the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA)

Placement of the logo of KhSA on the building of the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA)

Foto: Viktoriia Chumak

Placement of the logo of KhSA on the building of the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA)

Foto: Viktoriia Chumak

Where are you right now?

Iryna Matsevko (IM): We are hosted by the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA) and we really appreciate it. Our situation is unusual, because Ukrainian state and private universities rarely work in close cooperation. But the LNAA’s Vice-Chancellor and faculty are very progressive. They have let us their conference rooms to transform them into our studio space, although now they do not have space to run their big events anymore. Also, the LNAA has let us parts of their unused canteen, quite enough space for us to set up our workshops and administration there.

Did you get any other support?

IM: We can really feel a lot of support from the Lviv City Council and Lviv artistic communities. In return, we want to use our expertise to promote professional discussions in the city and to shape our vision of the education reform in Ukraine. Besides, our current stay with the LNAA is not just about getting shelter. We are actively cooperating with the LNAA: in the summer semester, we have already conducted joined internships, bringing together both our and their students, who worked together on the public spaces of the LNAA campus. Our School practises hands-on approach with real projects and real clients. And so, in the winter semester the LNAA will become our major client. In particular, our third-year students will work with the LNAA library to develop the philosophy of this place, making it a place not only for study, but also for communication and leisure. Also, the LNAA has plans to set up a modern canteen on the premises we are currently occupying. By this, our tutors will introduce a relevant project into our curriculum. This is the way for us to share our knowledge. We believe that our stay in Lviv will enrich both our universities.

Unloaded furniture at the new premises in Lviv

Unloaded furniture at the new premises in Lviv

Foto: Viktoriia Chumak

Unloaded furniture at the new premises in Lviv

Foto: Viktoriia Chumak

How did the evacuation of the whole school take place?

Daria Ozhyhanova (DO): We have relocated our school to Lviv, Ukraine, as it is impossible to continue teaching in Kharkiv. Kharkiv is only thirty kilometres away from the border with Russia and we guess it will not be safe there until the war ends. But we have responded to the situation very swiftly: just two weeks after the war began we resumed our classes online. Then we started the relocation process and tried to get all our students to Lviv before the end of the summer semester. Not all of them managed to come yet, but we are expecting them for the winter semester. At the moment, all the students are having their summer internship and afterwards they will go on holiday. Unfortu-nately, for different reasons, not all of our faculty members managed to come to Lviv to continue their work either: some could not come because of their families or because of a psychological trauma. After a while we have also evacuated our school equipment and the library. It was a logistic nightmare, but our team has managed it. All these boxes behind me are still waiting to be unpacked.

Oleg Drozdov (OD): We are now one thousand kilometres away from home, from our beautiful buildings, the faculty, our offices. It is quite a big challenge to change one’s life and setting like that. The hallmark of the KhSA is that most of our stuff is not only teaching but also working as architects. So, our relocation also meant relocating all the businesses associated with the School.

Preparation of doorways to standard sizes and laying of unnecessary openings in the premises of the non-functioning dining room of LNAA

Preparation of doorways to standard sizes and laying of unnecessary openings in the premises of the non-functioning dining room of LNAA

Foto: Maryna Samsonenko

Preparation of doorways to standard sizes and laying of unnecessary openings in the premises of the non-functioning dining room of LNAA

Foto: Maryna Samsonenko

How have the lessons and your work changed since the beginning of the war?

DO: This is a difficult topic. For sure, as a university, we felt our responsibility to react to the situation we found ourselves in, to the situation of war. It prompted us to rethink our BA programme and introduce new foci. We want to prepare the next generation of architects for working in the post-war context, which will shape their projects. But on the other hand, balance is paramount. Our students may feel disoriented, they may feel traumatised, because they have lost their homes. During the summer semester, we tried to arrange work in very small steps in order to adjust to the students’ pace and avoid traumatising them even more with overcomplicated tasks. Nevertheless, our students can feel that they have learnt things which will be useful for them in the future. For instance, in the summer semester, Iryna has already added a new focus to her course on heritage and its critical studies. That is very timely, considering the massive destruction of the cities and historic monuments in the Ukraine.

How did you proceed there, Iryna?

IM: Actually, when I was developing this course, post-war reconstruction was not on my syllabus. I had not worked in this context before. But I presented the topic in class and the students were interested in discussing various cases and reflecting upon the current situation in Ukraine. For the next academic year, I am designing a course on critical analysis of post-war reconstruction and its opportunities for Ukraine. It is important for the students to have solid theoretical footing and also to know how to approach the experiences of other countries critically. This discussion has already started in Ukraine and many architects have already been trying to take the best practices and bluntly apply them here. But for the KhSA it is important to develop our students’ critical thinking and their sensitivity towards the context.

Dismantling work in the premises of the non-functioning dining hall of LNAA

Dismantling work in the premises of the non-functioning dining hall of LNAA

Foto: Maryna Samsonenko

Dismantling work in the premises of the non-functioning dining hall of LNAA

Foto: Maryna Samsonenko

Will you also implement post-war reconstruction in the practical studios?

DO: Reconstruction and post-war studies have already become our new foci in the KhSA’s curriculum. We are also considering topics about technology, but the theory and tools for critical reconstruction will only be tackled earnestly by the third-year students. These topics are complex, the students have to be prepared to deal with them. In particular, the topic for the sixth-semester studio is reconstruction and adaptive reuse: a new topic, added as our reaction to the war. In itself, the BA programme is well-balanced and stable, we are actually quite proud of it. Its structure is very clear, but we have made several changes to its content. We have added the topic of post-war reconstruction in order to help the motivated students to understand and to be prepared for the future – which comes hopefully soon – when we all will be engaged in rebuilding and restoration.

OD: We have reshaped our programme and several aspects will be considered much more profoundly than before. Housing, for example, will become a super important issue for Ukrainian recovery, as well as urban planning and cultural heritage. These are quite specific things that the war has put forward as new priorities. In future, we will also consider starting an international MA programme. We have now started negotiations with several partner schools about designing a joint MA curriculum.

As Kharkiv is close to the border with Russia, did you have cooperations with Russian universities?

IM: Before the war, we cooperated with liberal architects with strong anti-Putin political views, who opposed the territorial process taking place in Russia. We successfully cooperated with MARCH, a private architectural school in Moscow. After the war started, as a university we voiced our belief that Russian society bears joint responsibility for the situation. Not only Putin, not only the people supporting him, but also liberals who are doing nothing to change the situation − these liberals are also responsible for the war. Presently, as a university, we do not have any contacts or relations with Russia anymore and this is our informed stand. Also, we refuse to participate in conferences or discussions, involving Russians. Our financial situation is challenging, but we refuse to accept any support from Russia nonetheless.

Summer practice of first-year students in the

Summer practice of first-year students in the

courtyard of LNAA

Summer practice of first-year students in the

courtyard of LNAA

What do you think of the Lugano conference on the reconstruction of Ukraine that took place in July?

OD: What such international events on the war in Ukraine indicates is that we lack a common lan-guage. It is as if each party saw the same thing somewhat differently. That is why we have formed our urban coalition Ro3kvit to develop a methodology for rebuilding Ukraine’s cities and infrastructure. Now Ro3kvit includes about 75 people, mostly from Ukraine, but also from the USA, the UK and the continental Europe. A lot of them are associated with the KhSA and some have experience in working with post-war context.

What do you want to achieve with Ro3kvit?

OD: Ukraine needs clear values and goals and also a methodology to develop the country. But it has to be a step-by-step process. One of the most important issues we are facing is to increase the capacity of Ukrainian construction experts and decision-makers. We will design projects to meet the urgent needs of the cities within the future development strategies. While learning from the past, we are developing new, future-oriented ways of co-creative organisation of urban design and sustainable development. We understand that old approaches are not working anymore and that the international experience cannot be directly transplanted into our situation without its re-thinking and adjustment to the context of Ukraine. First, we have to shape our vision. We need to understand and critically reflect on the new political, economic and social potential of the country. On the other hand, to make the introduced changes effective, there is a need to communicate and explain such revised approaches to all the stakeholders. Reconstruction decisions cannot come from above, they must evolve from the joint work of the experts, public authorities, civil society and entrepreneurs.

Will you also do research in the KhSA to support Ro3kvit?

OD: The Ro3kvit coalition works as a consultancy and as a visionary design team. The KhSA is one of the coalition co-founders together with the affiliated Kharkiv-based NGO “Architectural Education,” so many of our colleagues are associated with Ro3kvit; there is an ongoing exchange of knowledge and experience between all the participants. To be more specific about the activities, for instance, we started a KhSA laboratory for prefabrication technology, which can be useful in housing transformation. We also discuss reshaping the structure of the late-Soviet micro-districts, which are common for many Ukrainian cities. These are the topics studied by the KhSA as the leading research agency. At the same time, its team welcomes other Ro3kvit coalition members to join the work, while our colleagues also participate in other task forces. Besides, we are active participants of the public programme, so the coalition platform is an opportunity to get feedback about our work.

Public discussion in Lviv in May 2022. The Kharkiv School of Architecture: Architecture, War and

Public discussion in Lviv in May 2022. The Kharkiv School of Architecture: Architecture, War and

Education: (from left) Oleg Drozdov, Daria Ozhyhanov, Iryna Matsevko and Yulian Chaplinsy

Foto: Margo Didichenko

Public discussion in Lviv in May 2022. The Kharkiv School of Architecture: Architecture, War and

Education: (from left) Oleg Drozdov, Daria Ozhyhanov, Iryna Matsevko and Yulian Chaplinsy

Foto: Margo Didichenko

Oleg Drozdov is an architect, urbanist, artist and academic. He is a co-Founder, educational programme director and tutor at the Kharkiv School of Architecture. In 1997, he founded Drozdov&Partners architectural office and became its chief architect. Since 2020, he is a co-founder and the chief architect of the Paragraph studio of architecture and urbanism in Montreux, Switzerland.

Iryna Matsevko is a historian and the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the Kharkiv School of Architecture (KhSA). From 2008 to 2019, she was an academic coordinator and then deputy director and head of the public history programmes at the Centre for Urban History in Lviv, Ukraine. As the KhSA’s Humanities Block tutor, Matsevko designs courses on the cultural and social contexts of architecture, heritage studies and urban practices.

Daria Ozhyhanova is the BA Programme Director and Head of the 1st Year at the Kharkiv School of Architecture. She worked in the Portal-21 architectural office on projects such as reconstruction of historic buildings, public and private interiors. In 2016, as a participant of the NGO Urban Forms Centre, she coordinated a conference on gender issues in art, architecture and urban planning. She is a co-founder and architect of the NOEMA studio.

Placement of the logo of KhSA on the building of the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA)

Placement of the logo of KhSA on the building of the Lviv National Academy of Art (LNAA)  Preparation of doorways to standard sizes and laying of unnecessary openings in the premises of the non-functioning dining room of LNAA

Preparation of doorways to standard sizes and laying of unnecessary openings in the premises of the non-functioning dining room of LNAA